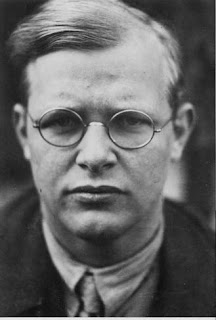

Dietrich Bonhoeffer developed an ethical praxis for Christian personhood, community and concrete engagement in the world while imprisoned by the Nazis at Tegel prison. By radically reshaping his Christology to conform to proper ethical action in the secular and fallen world, Bonhoeffer’s work from 1940 up to his execution witnesses the development of a complex “ethical theology.” The role of “the other” throughout this period, finding greatest expression in the Letters and Papers from Prison and Ethics, is a central motif and ultimately the main ethical obligation for man facing a world “come of age.”

This paper will examine the role of “the other,” and Bonhoeffer’s commitment to living for others in the development of his Christology, ethical theology and religionless Christianity project. Bonhoeffer’s martyrdom must be also understood in the context of this ethical theology, which was rooted in a deep commitment to living for the other.

Development of Ethical Theology

Bonhoeffer’s thought is often considered “fragmentary theology” and lacking clear continuity in both its theological and intellectual development. Karl Barth, a prominent theologian of the neo-reformation movement, from which Bonhoeffer was a member, remarked that Bonhoeffer’s later period of thought was a divergence from his earlier three periods (Shaping the Future 11 - 12). The first was a period concerned with an intellectual theology towards developing an actuality of Christian living with a highly structured pious life whose norms were given to it. The second shift in his thought was away from anything that took away the Christian from direct involvement in the world (Shaping the Future 13).

Personal friend and colleague Eberhard Bethge notes the continuity of Bonhoeffer’s thought was his continual emphasis on “churchly” and “worldly” matters. Throughout his work, the church and the world were always in a dialectical tension, singularly emphasized in the light of the significance of the moment (Bonhoeffer’s Theology 280). It is clear that Bonhoeffer’s divergence in this dialectical interplay changed dramatically after 1940. By 1940, Bonhoeffer’s experience in prison shifted his thought away from issues of the church in both the visible and invisible forms. As his theology began to set aside attention towards ecclesial matters, it dramatically shifted emphasis towards direct participation in secular reality. According to Bonhoeffer scholar John Phillips, Bonhoeffer separated himself from ecclesiology in order to fully open his theology to “his conviction that the revelation of God in Jesus Christ was visible, tangible, concrete, apprehensible by all men” (Christ for Us 28).

Bonhoeffer’s religionless Christianity project was concerned with defining the existential predicament of the Christian mind and existence in a world which had reached adulthood. In response to liberal notions of the death of God, Bonhoeffer adapted a unique position for man in a secular world “come of age.” To Bonhoeffer, God had retreated from society and was no longer the working hypothesis of reality. While commenting on and responding to a whole host of intellectual and theological concerns in the Ethics and Letters and Papers from Prison, Bonhoeffer’s work is often viewed as a commentary on the Christian Church in an era that had “become conscious of itself and the laws which govern its own existence” (Ethics, 23). In the context of his Christology of living for others, Bonhoeffer developed a broad ethical theology that adapted to the situation he found himself in under the Third Reich. The death of God as developed in the Ethics brought the concern of God back to the present situation, “God of beyond is not of our concern, but it is with God in this world, as created and preserved, subjected to laws, reconciled and restored” (Ethics 21).

Bonhoeffer’s personal motivations and feelings about his situation in prison are difficult to relate to his ethical and theological thought. Everything he wrote was intensely reviewed by the Nazis. Throughout his experience in prison, and especially after it became clear he would eventually be implicated in the assassination plot to kill Hitler, Bonhoeffer never referred to his own suffering. In addition to this constraint, Bethge remarked that Bonhoeffer’s temperament was reserved; rarely did he reveal in personal correspondences what he was feeling (Bonhoeffer’s Theology, 275)

During the Tegel prison experience, Bonhoeffer developed a distinct “theological ethics,’ and praxis for living in the world which resembles liberation theology. There are two main differences between it and liberation theology: the first is in liberation theology a particular social problem such as poverty or the liberation of oppressed people’s is sought, whereas ethical theology opens a broader scope enabling a wider range of ethical issues to enter. Secondly, ethical theology is not concerned with identifying who is and who is not a Christian, but seeks identification through confession of Christ as savior (Shaping the Future 59). Ethical theology proclaims that concern for one’s neighbor can never be set aside.

Bonhoeffer’s ethics were inherently a response to the present situation and he denied idealist, or timeless and placeless ethics. Since Christ was the last word in temporal and physical reality, every present situation is broken from and dissociated from its past and history. Bonhoeffer replaced idealist ethics with an applied ethics of the situation and engagement in the real world. Marsh disagrees that Bonhoeffer’s ethics are “situational,” stressing that his ethics emphasized spontaneity, not structure in ethical action. To Bonhoeffer, the present situation did not reveal any pattern, nor were there formulas for making decisions in the world (Shaping the Future 15 - 17). The whole world was already reconciled in Christ, rendering all ethical concerns with the here and the now. We will discuss the role that this-worldliness played on Bonhoeffer’s eschatology and ethical action later. To Bonhoeffer, man must conform himself to the structure of Christ in the world, a structure that enables man to live for others.

Non-Dualism in Christ

To understand Bonhoeffer’s platform of ethical theology we must understand his strong aversion to Christian dualism. To Bonhoeffer, the Christian mind had practiced an epistemology split in two poles, on one was the profane, fallen and secular world and on the other was the risen, holy Christian community. It is important to note that Bonhoeffer denied “two sphere thinking” in the context of his own eschatological position on the present situation. In Reclaiming Bonhoeffer, a book about Heidegger’s impact on Bonhoeffer’s theology, Marsh notes four essential themes in Bonhoeffer’s reading of Revelation. Revelation must challenge and constrain the self, be independent of its being known, and confront the self in such a way that the person’s own relations to and knowledge of others are based on and suspended in a being-already related to and known (Reclaiming Bonhoeffer 128 - 130).

Bonhoeffer’s attack on Christian dualistic thinking extended to other major critiques of Christianity such as passivity and submission. Similar to the neo-orthodox theologians, Bonhoeffer was opposed to modern pious liberal Christianity which separated gospel and law, spiritual and political, internal and external (Bonhoeffer’s Theology 274). Bonhoeffer even compared the pious church to the individual Christian’s submission in the face of Christ’s calling.

The ultimate source of unity that could overcome the split church and split mind of modern Christians is Christ’s conformation. Conformation and non dualism was concerned with centering man with Christ, but not Christ of the liberal pious type, but Christ-the-man. Christ-the-man was the key to unlocking the non dualistic nature of reality. Conforming to Christ-the-man centered one’s existence with the world come of age. Christ-the-man presents an overabundant unity of life, and a rich polyphony of living. This molding of man in “Christ as structure,” was what Bonhoeffer referred to as conformation; the concrete molding of personal and social life to the reality and pattern of the incarnate lord Jesus Christ (Shaping the Future 15 - 17). While Christ was the answer to Christian dualism, his calling still divided the world. Bonhoeffer saw the world as divided between those with Christ and those without Christ, “He that is not with me is against me” (Matthew 12:30).

Bonhoeffer conceived of the Christian unified in Christ as the hallmark of freedom to live for one’s neighbor. Once man was conformed in Christ, one is able to “sin boldly.” In an essay entitled Civil Courage?, Bonhoeffer remarks in the Letters and Papers from Prison,

“…it depends on a God who demands responsible action in a bold venture of faith, and who promises forgiveness and consolation to the man who becomes a sinner in that venture” (Letters and Papers from Prison 29).

When conformed in Christ’s unity man is able to risk boldly and take decisive actions for others.

Bonhoeffer developed another important dichotomy between concerns for the ultimate and the penultimate. As early as his work on Sermon on the Mount in The Cost of Discipleship, Bonhoeffer stressed that the Sermon on the Mount was meant to be, “not a vague set of ideals but a hard, specific demand on the crucified and risen lord upon the disciple” (The Cost of Discipleship 211). In Ethics, this focus on the ultimate resurged in his thought. The ultimate was the Gospel proclaimed, studied and the Word of God in the manhood of Christ. The penultimate was the Biblical feelings of guilt, transcendence and resurrection that the modern Christian had lost touch with. The present age Christian had to come to grips with the radical message of the resurrection in order to center their existence for Christ and the other (Bonhoeffer’s Theology, 242 – 245).

Achieving Christ’s wholeness of life required interdependence with ones neighbor. Christ had to be understood in the same position as secular man and as the religionless Christian; completely autonomous and free to live for others. Bonhoeffer stressed the dual nature of understanding the ultimate in Christ, “I do not know the man Jesus Christ unless I can say Jesus Christ is God, and I cannot know God unless I say Jesus Christ is just a man” (Bonhoeffer’s Theology 245). Nowhere is this notion of living for others in accordance with Christ-as-man more clear in Bonhoeffer’s “self-less self love” letter to Bethge. The letter was a challenge to modern secular versions of altruism and egoism. “Strength of character involves realistic self acceptance” (Bonhoeffer’s Theology 268). The genuine religionless Christian loves his neighbor as himself, allowing him to exist as a human being in his own right. In this letter, Bonhoeffer discusses the roots of sin as revealed in scripture come not from man’s weaknesses, but from his strengths. The hunger for power, and pride were worse than weakness. The weak person could overcome the weakness within himself through self discipline and living for others.

Living for Others “Between the Times”

Responding to the fallen world and preparing the way for Christ’s return was the basis of Bonhoeffer’s Christology and religionless Christianity project. While living “between the times,” in the tension between the old creation and the new creation, the secular age and secular man was more similar to Christ-the-man than the Christian. Secular man was a being to emulate, just as Christ was to be emulated. For a man imprisoned and facing inevitable death, Bonhoeffer’s eschatology is remarkably this-worldly. His reading of the book of Revelation was concerned with “things before the last,” not with those after the last. Very seldom do Bonhoeffer’s writings focus on ethereal or other-worldly matters. The death of religion and the religionless Christianity project rendered humankind as out of touch with the ultimate Biblical feelings of guilt, transcendence and eternal life. These ultimate Biblical concepts were what man had to reorient to in order to prepare for the last things and the return of Christ. Bonhoeffer fit the world come of age into his eschatology to relate the Old Testament to the secular Christian. “It is quite clear that the preparation of the way is a matter of concrete interventions in the visible world.” Yet, he adds that it is priority to “reform earthly conditions, but it is (more) a question of the coming of Christ” (Ethics 91).

In elaborating on the archetypes of the present age, Bonhoeffer identifies the existential and spiritual limitations of “secular man” and the “religionless Christian.” Interestingly, both archetypes were already in metaphysical balance with the salvation and suffering in Christ’s name. Yet, they were unconscious of their similarity and still needed conformation in the incarnate and risen lord to prepare for Christ’s return. Bonhoeffer deified secular man as living as Christ had lived; completely autonomous and utterly a man, stripped of divinity. The sign of the world’s adulthood was the retreat of God in the public sphere, “we can live without God and in more reverence for God because God has trusted humanity to live without him as a working hypothesis. We live before God and with God we live without God” (Ethics 194). Living without God meant that we have to learn to live as ourselves for others.

When we live as ourselves we are able to live for our neighbors and live in preparation for Christ’s return. Bonhoeffer discussed the centrality of living for others in his conception of the “social sphere of persons,” and the collective person. In the Ethics, man is always faced with a situation of relationality (we live with one another) and responsibility (we live for one another). The idea of the “collective person” and the responsibility of living for one another is articulated in Bonhoeffer’s dissertation, the Communion of Saints, and it was adapted to the religionless Christianity project. John J. O’Donnell’s conception of the Trinitarian perspective describes Bonhoeffer’s perspective:

“God is neither supreme object over against humanity nor the supreme Thou depending on the human I for fulfillment. God is in his own life interpersonal communion, and because God in his own being is love, God can be love for us, a love which is free and gratuitous. The love which is God is overflows into creation and time” (The Mysterey of the Triune God 161).

In Christ, the I is drawn out of itself to live for the other, into the “social sphere of persons” (Ethics 128). Without Christ, my neighbor is no more than the possibility of my own self-assertion. Christ enables the self to participate in the love of God himself in Jesus Christ, who is the mediator of all genuine, agaepic love. God in this sense is the divine subject self-witnessed in the presence of Christ as community. Since God in his own being is love, God can be love for us. “Where the I has truly come to an end, truly reaches out of itself, there is Christ at work” (Act and Being 160). Those who are in Christ are free to live for and with the other. Bonhoeffer took the idea of the self as reshaped in Christ as a self for others to the farthest degree possible, “it is never a case that the concrete person is in complete possession of himself” (Reclaiming Bonhoeffer 117).

A key component to the responsibility of living for one another was that God’s love ultimately seeks out the other. The individual self had a reciprocal duty to seek out the other in communion with the real world. Man in the present age should seek communion not in the divided and “scattered church” but through engagement with reality. As he had done to “secular man,” Bonhoeffer deified the real world and proposed that engagement in it was sacramental. Since the world was fallen and “God is in the facts of the world,” the religionless Christian is to find communion and grace with the “thou” in the “it” (Reclaiming Bonhoeffer 128). Through accessing the reality of the world and living dangerously for others in it, man is free to participate in the world which is “loved, condemned and reconciled in Christ” (Shaping the Future 88-89). If mankind is not rooted in a Christology that placed Christ-as-a-man, the individual is not ready and receptive for God’s revelation.

Ethics of Living for the Other in the Moment

Much has been written about Bonhoeffer’s this-worldliness and principled action in the present situation. More recently, scholars have shed a more complex light on his role in actively responding to injustice and oppression around him (Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Response to Nazism 100 - 103). Bonhoeffer’s actual ethical writing after 1940 do present a radically changed perspective, deeply committed to concrete intervention in the world. As outlined earlier, Bonhoeffer’s ethical theology brought the widest scope possible to bear on social injustice with the purpose of enabling man to live for his neighbor. Living an authentic Christian life for others amidst a secular world come of age and the atrocities of the Third Reich manifested a deep seated commitment to social justice in Bonhoeffer’s ethical theology.

To Bonhoeffer, social injustices prevent people from hearing the ultimate word of grace. He assessed the present state of Germany and his role in the Resistance Movement as a matter of moral chaos, not as a situation caused from the rise of conservative politics (Shaping the Future, 100). His strong belief that solutions must be sought through careful Christian practice is clear throughout his life. Remarking on what is to be done in the present situation, Bonhoeffer remarks, “everything depends on this activity being a spiritual reality, precisely because ultimately it is not indeed a question of the reform of earthly conditions, but it is a question of the coming of Christ” (Ethics, 96).

His ethics do not proscribe what is right and good, but rather dealt with the will of God. Since the will of God could be accessed in the real world, specific attention to a particular injustice was parochial and not within the wide panoply of theological concerns (Shaping the Future, p. 15). This is not to say his ethical theology avoided concern with the plight of the Jews, for instance, he remarked, “only he who cries out for the Jews may also sing Gregorian chant” (Bonhoeffer’s Theology, p. 248). Bonhoeffer was a deeply committed theologian who placed almost ideological value in his ethical maxims.

Classifying Bonhoeffer’s Martyrdom

Bonhoeffer is often considered a martyr, but it is difficult to identify the psychological and ideational dimensions of his martyrdom. Drawing on the universal definitions of martyrdom by Kierkegaard helps to establish a coherent classification of Bonhoeffer’s actions. Kierkegaard considers all martyrdom to be a social act which is above all a metaphysical and psychological classification, and he continues, “it defies all analyzable practical implications” (Religion and Violence 10). Bonhoeffer’s ethics of action and martyrdom are strikingly similar to Kierkegaard’s definition of the act of martyrdom. To Kierkegaard, “the act of martyrdom is for recognition of the other, which is not based on public opinion, but an absolute instance followed by an equally absolute act of instantiation in need of being repeated ad infinitum” (Religion and Violence, 162 - 167). The here-and-now reality of any engagement in the world is a sacrament capable of bearing the infinite. Bonhoeffer’s infinite engagement with reality in the sacrament of the real and fallen world fits Kierkegaard’s definition of martyrdom. Because God was in the facts of the ‘fallen’ world, participation in the world held sacramental value ad infinitum. To Bonhoeffer, the Protestant had for too long considered suffering in spiritual terms, and had lost all connection to bodily suffering. Similar to Kierkegaard’s conception of Christian suffering, the late Bonhoeffer believed suffering itself was contingent on a divine ordinance (Bonhoeffer’s Theology, 274 – 275). Bonhoeffer read Kierkegaard’s The Sickness Unto Death and Fear and Trembling in his own last days in Tegel prison.

Both Christian thinkers consider grace and suffering as central to Christian living in the world. For man to enter grace with others, the Christian must first cultivate a “consciousness of sin.” Consciousness of sin must be felt through engaged suffering in the world. Suffering is a necessary component for the Christian in both Kierkegaard’s and Bonhoeffer’s dialectic of grace (Kierkegaard as Theologian 104). Bonhoeffer believed it was incumbent on all Christians to practice an active interiority of sin by emulating the suffering that Christ provided the perfect model for imitating on the cross. Speaking about the role of suffering for the Christian, Bonhoeffer remarks, “this assurance that in their suffering they will be as their master is the greatest consolation the messengers of Jesus” (Bonhoeffer’s Theology 273). Indeed, the cross was the present age’s chief symbol of otherness. Christ’s act of sacrifice on the cross enables us to see the full cost of reconciliation between God and world (Shaping the Future 123). Late in Bonhoeffer’s prison sentence, he describes the interplay between suffering and freedom,

Not only in action, but also suffering is a way to freedom. In suffering, the deliverance consists in our being allowed to put the matter out of our own hands into God’ hands. In this sense death is the crowning of human freedom. Whether the human deed is a matter of faith or not depends on whether we understand our suffering as an extension of our action and a completion of freedom” (Letters and Papers from Prison 206).

Bonhoeffer’s ideational and psychological martyrdom are difficult to classify as his unique theological ethics overshadow simple classifications. Added to this complex understanding of his own martyrdom is the highly censored material from the prison writings, which reveal little of the inner feelings and motivations of the person of Bonhoeffer.

Drawing from Kierkegaard’s notion of the spiritual martyr sheds insight into the general structure of Bonhoeffer’s martyrdom. For Kierkegaard, spiritual martyrdom deals with the idea of seeking freedom from an oppressive temporal world. Bonhoeffer sought freedom through death for transcendence to God, “whose service is perfect freedom” (Bonhoeffer’s Theology 277). The Kierkegaardian martyr seeks to access the freedom of the temporal through suffering. In participative suffering in the world, the martyr opens up a cleavage between time and eternity, where the martyr transcends the temporal and enters the eternal. Upon his death, Bonhoeffer connected with the notion of the eternal and escape from the oppression of the temporal,

God will see to it that the man who finds him in his earthly happiness and thanks him for it does not lack reminder that earthly things are transient, that it is good for him to attune his heart to what is eternal” (Bonheoffer, Letters and Papers from Prison 111).

Bonhoeffer’s idea of escape from the oppressive temporal and physical world was molded into his unique Christological position on the last things before Christ’s return. Bonhoeffer prepared himself for transcendence from the transient into the eternal. His later reflections in Letters and Papers from Prison indicate a deep level of internal preparation for his impending execution. For all of Bonhoeffer’s this-worldliness and attention to the sacrament of the real situation around him, which was in utter ruin and destruction, his last words indicate this notion of transcendence from the temporal into the eternal, “this is the end, for me the beginning of life” (Bonhoeffer, Letters and Paper from Prison, 203).

Conclusion

Bonhoeffer developed multi layered praxis for ethical engagement in the world which placed living for others as the central obligation of humankind. All of his theological concepts flow from the Christological call to live for others. The religionless Christianity project sought to open spaces otherwise closed to humankind for proper relation to ones neighbor. The non Christian and the Christian molded by the pious and liberal institution of Christianity could learn from the non religious Christian archetype the proper ways to fully exist in preparation for the last things in Christ.

Throughout his ethical theology and writings in prison, Bonhoeffer began to show clear traits of Kierkegaard’s structure of the spiritual martyr. Although much of his thought and ethical action are problematic in light of his role in the Resistance Movement, his theology consistently established a commitment of living for the other through direct engagement in the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment